When Amazon opened its first Amazon Fresh grocery store in Ealing last month, much was written about how it offers a ’till-less experience’ where customers can simply pick up the items that they’ll like to buy and walk out when ready. All purchases will then be charged to their Amazon accounts when they leave the store. This experience is enabled through a combination of shelf sensors and powered by a multitude of cameras and AI-based people tracking to determine ‘who picked up what’.

Whilst this news was greeted with much discussion of what sort of competition Amazon would bring to the low-margin, high-volume grocery retail business, perhaps less noticed was the fact that Amazon is not just competing as a physical retailer, it is also offering the technology to established retailers through branded as “Just Walk Out – technology by amazon”.

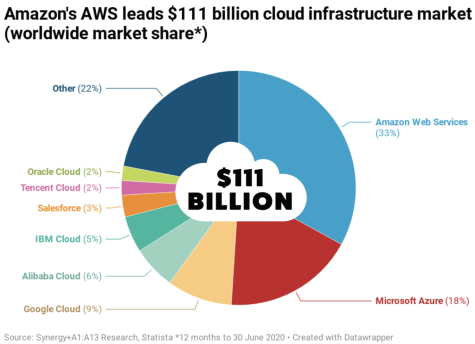

Of course, Amazon has good form here, it started selling the tech behind its online retail business in 2006, when it launched its cloud computing platform, the first service of what was to become its AWS offering. Today, AWS represents 12% of Amazon’s revenue, but 59% of its profit.

While Amazon is perhaps the best example of companies creating more value out of their tech than by selling the products that were the core of their business, this strategy has a fairly long and distinguished history. In this post, I explore some of the drivers and strategies pushing companies down this direction.

1. Mobile Network White labelling – No longer just a business on the side

Creating products or technology that are white-labelled, in other words, suited to be sold and marketed by a well-known brand is nothing new. Indeed, it long has been one of the main pillars of the Chinese consumer electronics export industry. But what when the reverse happens? Consider the case where well-known brands sell their technology to other companies, even to their competitors.

Mobile virtual network operators – mobile operator brands making use of another company’s network infrastructure – offer one of the best examples of this type of white labelling. Mobile networks are notoriously and inevitably capital intensive businesses, requiring large investments in the network infrastructure to provide nationwide coverage and capacity as well as fees to governments for access to mobile spectrum.

This has two implications. First, profitability hinges on maximising utilisation and return on these assets, and secondly, any market can naturally support no more than three or four mobile operators. This situation naturally lends itself to mobile operators offering use of their infrastructure to other brands and companies for whom a mobile telephony service is a good match for their brand or existing customer offering but clearly could not justify the investment.

In the UK, brands like Tesco, Giffgaff, Sky Mobile, TalkTalk were all established as virtual operators, and today represent approximately 30% of mobile customers. For O2, a full 38% of its customer connections are now provided via other brands including giffgaff, Sky Mobile, Tesco Mobile and Lycamobile, showing how this is no longer a little business on the side, but is a key contributor to the company’s core operations.

2. Ocado – Pivoting to become a tech startup

Ocado has been well-known in the UK as an online groceries retailer, a business that has grown by over 40% over the last year [2] as Covid restrictions meant that households shifted in droves to online shopping. As impressive as this growth appears, this represented a tiny 1.7% of the overall UK grocery market share.

In financial terms, in 2020, Ocado made a revenue of £2.2b with an EBITDA margin of 6.8%, equivalent to £149m. Whilst this is a respectable performance, providing margins that are broadly similar to those of Tesco, a leading UK supermarket, though bsased on much smaller revenue compared to Tesco’s £65billion. So far so good, until you realise that although Tesco generates more than 33 times as much cash as Ocado’s retail operations, the valuations of the two companies are relatively similar, at £17 billion and £15 billion respectively.

So why is Ocado so much more valuable on a like-for-like basis? The difference is that Ocado does not see itself as retailer, but rather as a provide of online sales and fulfilment technology to the grocery industry. In an opinion shared by the stockmarket, Ocado is not a retailer, but rather a tech company, selling highly automated warehouses (known as Customer Fulfilment Centres in its parlance) and other online technology to well-established grocery retailers to assist them to go online. As an example, Ocado signed up Kroger, America’s largest supermarket chain to provide its technology in twenty new CFCs, and has also struck similar deals with supermarket chains in France and Japan, just to mention a few markets.

These fulfilment centres host robots the size of washing machines, all connected by a private 4G network, criss-crossing a grid of algorithmically-placed products. They whizz around the warehouse collecting the orders and delivering them to pick stations where the customer orders are collected for dispatch. Ocado is proud to show off the tech, to further burnish its credentials as a tech company. Pivoting to position itself as a tech company, not only allows Ocado to become a global player, frees itself of the notorious challenges faced by supermarkets in international expansion, but also allows it to play in a much more differentiated, higher-margin business. It also helps that thanks to Covid, this is also a rapidly growing market.

3. PayPal – when the spin-off outgrows the parent

Ebay and Paypal have a long and convoluted history. Both children of the original dotcom boom, Paypal’s business hinged primarily on payment volumes on eBay’s auction website. It proved attractive to both buyers and sellers. Buyers were provided with protection when paying small sellers as they did not need to provide them with their credit card details, while sellers were now able to accept online payments, even though they wouldn’t necessarily qualify for a credit card merchant account.

When PayPal went public in 2002, it was almost immediately acquired by eBay for $1.5 billion who saw it as a core to their success as an online auction company. Nevertheless, just over a decade later, institutional investors were clamouring for a demerger. Although PayPal was the most successful online payments system, successfully challenging the established credit card networks, its shareholders felt that it was being unnecessarily shackled by being part of eBay, which was performing poorly in comparison to Amazon, the giant on online retailing.

Sure enough, since the spin-off, PayPal has flourished. Much like the strategy Ocado is currently trying to pursue, PayPal’s payment platform was able to generate greater value beyond the confines of the eBay marketplace by offering its technology to its erstwhile competitors, allowing it to achieve a scale comparable to that of the credit card companies. Through a series of acquisitions, PayPal has fast become the most complete Internet-based payments platform and digital wallet, benefitting from network effects, where “winner takes all.” The markets agree. Since the demerger, the stock price of Paypal increased by 527%, while that of eBay a somewhat more modest 22%.

Conclusion – Amazon sets the benchmark

This brings us back to where we started this post. To Amazon, which is really the technology provider par excellence. There are few businesses where it is engaged in where it is not prepared to commercialise the technology it builds for its own products. Although the first AWS products hark back to 2006, Amazon was selling its e-commerce tech before that, famously providing Marks & Spencer with the stack for its online store in 2005.

Since then, its cloud services have expanded to include over 200 services, many of which were developed for its own applications. You therefore find voice synthesis toolkits as used by Alexa, facial recognition services and so on. Its Prime Video product not only showcases content sourced by Amazon, but offers other content providers with their own channels in the platform. Therefore you see the likes of Hallmark TV and Eurosport appearing in Prime Video. In the physical world, its “Fulfilment by Amazon” provides sellers with access to its warehouses and Prime delivery and customer base.

Through this strategy, Amazon is able to generate a far greater return on its R&D investment that it can by keeping the tech to itself. By selling the tech to other companies, Amazon can generate incremental high-margin revenues to assist with this growing investment. Often, the companies Amazon sells its tech to are competitors insofar as they operate in the same industry. However, in most cases, they simply don’t have the scale, distribution excellence, market reach or technical prowess to remotely be a competitive threat to Amazon. They are not in the same league. They are simply customers.

Read More

- Virtually Mobile: What drives MVNO Success, McKinsey&Company

- Ocado achieves largest market share of all time as online grocery sales jump 91%